Gamification in education – constructivist classroom activities with Sven Heckele

Table of Contents

This amazingly detailed piece was sent to us by a good friend of Explain Everything, Sven Heckele, an English teacher and Tech Coordinator from Germany. We absolutely had to share Sven’s insight with you – his perspective, based on years of classroom experience, can be an inspiration for teachers of children of any age. So without further ado, we yield the floor. We hope you enjoy it as much as we did!

Gamification to support constructivism

To explain how I view the use of gamification to ensure constructivism, I’d like to first take a small detour to showcase Daniel H. Pink’s thoughts on motivation (found in his excellent novel “Drive”), and how they are at the core of my game.

Daniel H. Pink outlines three pillars of modern motivation and aptly names them Purpose, Autonomy and Mastery. To explain how gamification hits all of these areas, it’s important to understand what gamification is.

Gamification is the use of game mechanics in areas that are not originally game-related. In the case of school, this means intentionally adding layers of playfulness and various other mechanisms on top of your curriculum in order to tie together somewhat loose lessons or units into one bigger, more cohesive experience for students.

Theme as the most important part of gamification

Arguably the most important issue to figure out early on is what’s referred to as a theme. Teachers should pick a theme that doesn’t just interest them, but one that they are passionate about, because seeing your passion shine through your work and creations is a big part of what will inspire your students to delve into your game. In a way, the theme is both the framework of your game and the glue that will tie all of the various features together.

The theme I have chosen is a medieval fantasy world ripe for exploration. The story, at its core, is a simple one: a calamity 300 years ago caused some kind of tectonic event that separated the Tower of Nuvoro from the rest of the world. Due to terrible harvests in the previous season, a band of young explorers has to brave the sea in search of a food source. All they know about the mainland is this: the people living there used to speak English 300 years ago. Hopefully, they are willing to work with strangers and help out in the explorers’ quest for food.

Even a simple story can get students engaged

That’s pretty much the entire main plot. More of the story unfolds in minor quests. On day one, students are presented with the choice of becoming one of four character classes. At first, there doesn’t seem to be a big difference between them, but as the game progresses and more abilities are unlocked, each class will develop its own visible strengths and weaknesses.

This initial meaningful choice of choosing your own character and setting out on your journey covers two of Pink’s pillars. The story strikes a chord with purpose.

Students are no longer just sitting in the classroom, reacting to the information being thrown at them but are now part of a band of explorers embarking on a journey. That may not sound like much at first glance, but it gives students both purpose and agency – and imagination is one of the things we most underestimate about our students. This is what engages students.

Autonomy starts right off the bat, on day one, as students are immediately presented with a meaningful choice. They have access to four options, and whichever path they choose, they will leave three roads untaken. How often do we challenge ourselves to present our students with real, meaningful choices?

Gamification for interactive learning – the importance of wording and optionality

The theme, I must add, isn’t just limited to the story, it’s also expressed in the visual style you’ll choose to use for any of your creations, be it a thematic explainer video, a thematic worksheet or even just a thematic background for your device. One of the richest forms of showing your theme is using unique language. If you’re at a school that does homework, then consider not calling it homework anymore but calling it a bounty, a quest, a mission – whatever suits your theme.

Mastery, to me, is where gamification really shines. My students get to show their mastery by doing side quests. Roughly 90% of my curriculum looks exactly the same as it did before I gamified. I sprinkle in the occasional fully gamified lesson here and there, but – as I’m still new to gamifying – not too often just yet.

Adding more and more such lessons is a goal I’m working towards, but nothing I plan on rushing through. Where my game really shines, however, is side quests. Side quests are completely optional assignments that students do NOT have to do, and I make that clear to them – the side quests are not obligatory and do not directly affect their letter grade at all.

Side quests instead of tasks for more engagement in the classroom

This is where the magic happens. Because they are optional, I view these tasks as invitations. I try to think of a fun activity that includes my subject (English – or ELA, as some might call it). And I usually try to steer clear of traditional school assignments such as “Write X”. Instead, I try to get them to use their creativity. As an example, I may provide the students that are willing to take on a side quest with a coloring book drawing and explain in English which part I want colored in which color. In such an example, I use images that are easy to understand while using new vocabulary, words that they do not know yet. It’s important to note that I don’t explain this new vocabulary to them. That’s up to them. It’s their learning. Once the drawing is done (and rewarded with experience points that will help their character reach the next level, strengthening their abilities in the game), they are invited to do part two. Part two in this particular series is actually building what they drew any way they feel comfortable.

This is where they can really get creative. They can build, say, a ship, using Lego bricks or cut-up styrofoam or cardboard, or they can build it digitally using a presentation tool or even Minecraft. The sky’s the limit. Just do something fun and create something! The connection to the lesson itself? Virtually zero. But it invites and allows them to be creative, to try something they may not have tried otherwise.

And then comes Part Three. Here, I just ask them to write ten sentences about what they just created – any ten English sentences will do – for a reward that’s nearly triple what the first two parts were worth. A rather uninspiring task compared to the first two, but because they are already two-thirds of the way done, why stop now? So this is where mastery of the subject matter starts to peer through. I openly manipulate my students into thinking about my subject in their free time and through doing so, I try to offer them some fun, too.

If they choose to take up my invitation, they’ll practice their English a little bit. No direct effect on their grades, but, as one can imagine, students doing quests tend to be better at English after they’ve done a few simply because they’ve practiced their language skills more and have been exposed to the material more than students that choose not to participate.

A constructivist classroom – challenging students and using edtech

This is where technology comes in. My three-part starter quest intentionally has a very low entry barrier. It’s intended to show students that side quests are simple, fun and different from regular school. And because they are optional, I do not feel the need to explain them too much. At the end of the day, I kind of want my students to just run with it and make their quests their own. This spirit is kept alive in subsequent quests, too. Future quests will invite my students to maybe digitally enhance or alter an image, to create and edit a video, to try out a new tech tool or to create a presentation. And none of those requirements will come with overly detailed instructions – so if students choose to go on a quest, they’ll know that the sky’s the limit. If they want to record a short 30-second clip, that’s great. If they really get into it and end up creating a 5 minute video complete with a little story, all the better. Both projects will receive praise and will ultimately serve to increase students’ self-esteem.

This will give a platform to students that might not normally speak up in class, and it will also create moments when someone does something so interesting that their classmates will ask them how they did it, and perhaps even to teach them.

Students becoming creators – the final goal of my gamification

All of this, getting back to my original point, is where constructivism comes into play. Students have a chance to become creators, and the more quests they participate in, the more they will take ownership of their learning. Quests are never graded, nor are they checked for errors. They’re valued for risks taken, for initiative shown and for works created. The more students have experienced, the more they have learned.

That, to me, is the beauty of gamification. Each student gets to choose their own level of commitment to the game, to their learning. Friendships are built, skills are honed and new passions may be discovered, all in a playful, safe environment. Relationships, passion, community – all of it enriches students’ learning, and yet all of it is part of the game.

How Explain Everything helps me keep track of various data points

Gamification isn’t hard, but it is a big time investment. To me, it’s worth every minute but streamlining is something that is very, very important to keeping the game alive. I have created a card game that is mostly physical. I love getting to hold a card (I print my card, have students help me cut them all out, laminate them and have students help me cut them out yet again) in my hand, looking a student in the eye and praising them for something brave they did or awarding them for a great feat done. Because I’m just handing out a piece of paper, it’s entirely up to my discretion how and for what I use them. But it is just so special, when I can give a physical object to a student, saying “Wow! I can’t believe how hard you worked on your project. It really shows how much time and passion you invested in it!” That is forming a relationship, valuing a student, seeing them. That’s a moment students can remember, can cherish. That’s the kind of moment I did not use to have.

But both the need for hybrid lessons as well as the fact that not all students are equally organized means that playing a battle with various player cards can quickly become very time-consuming – and time is as valuable in a gamified class as it is in any other; possibly even more so. In comes Explain Everything.

Gamification in the classroom with Explain Everything

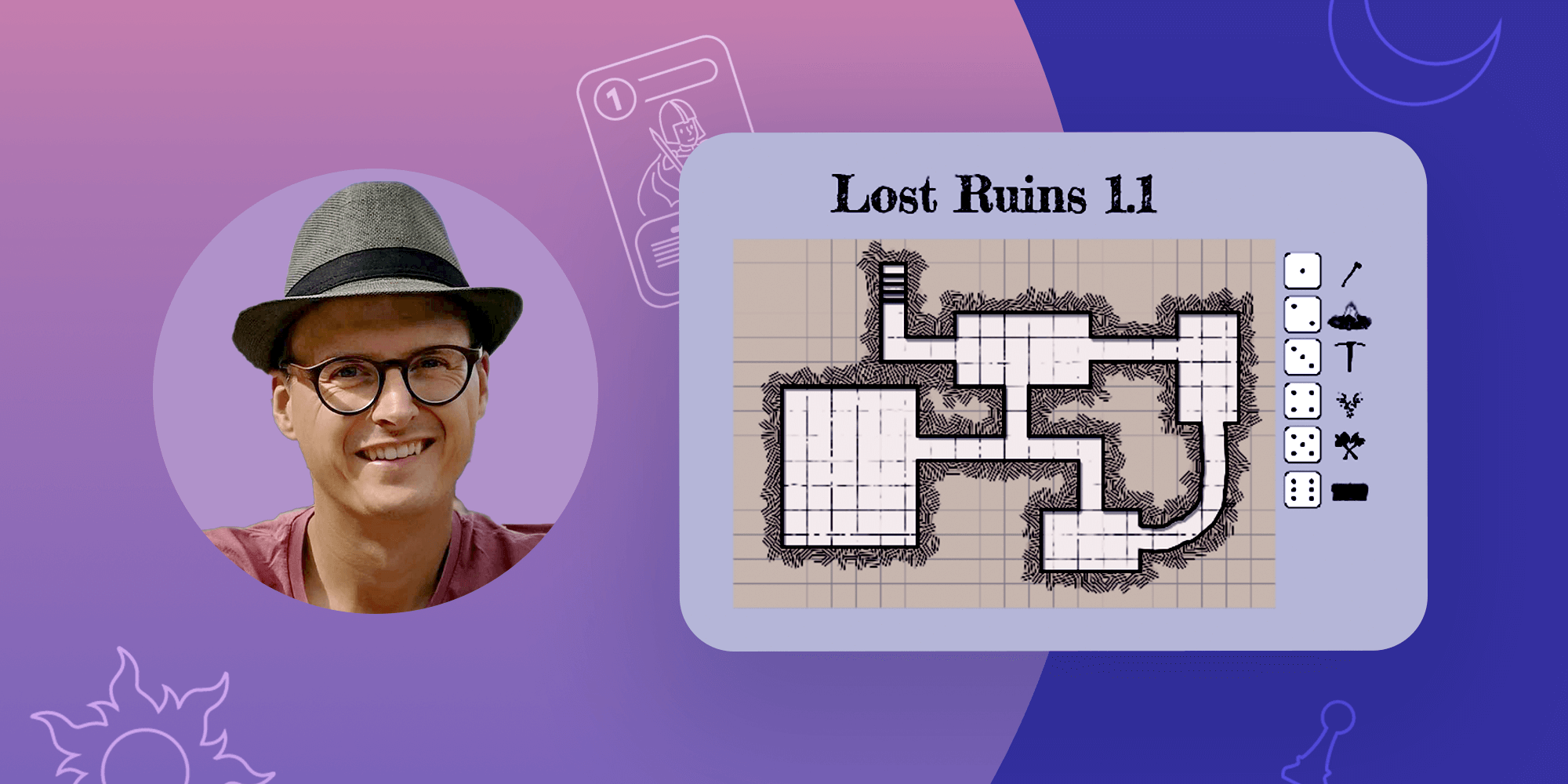

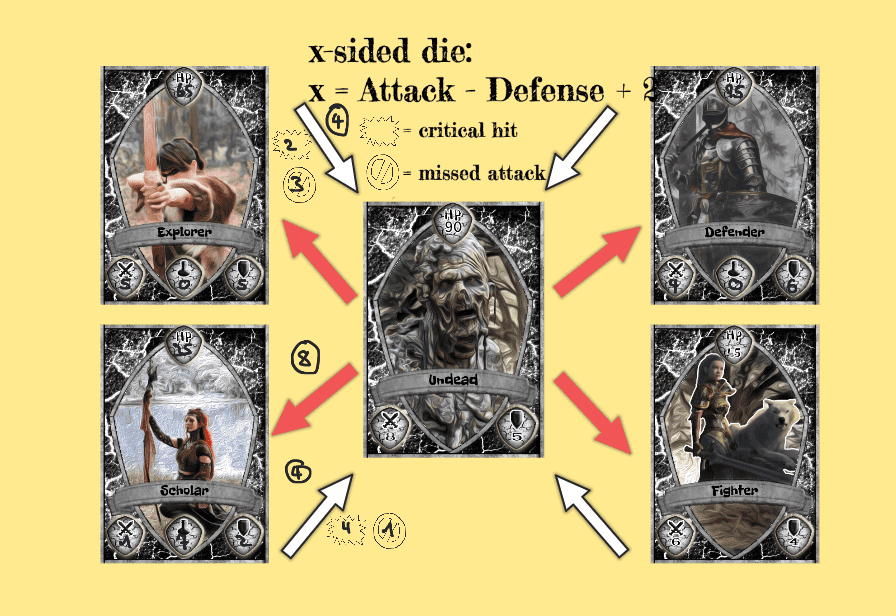

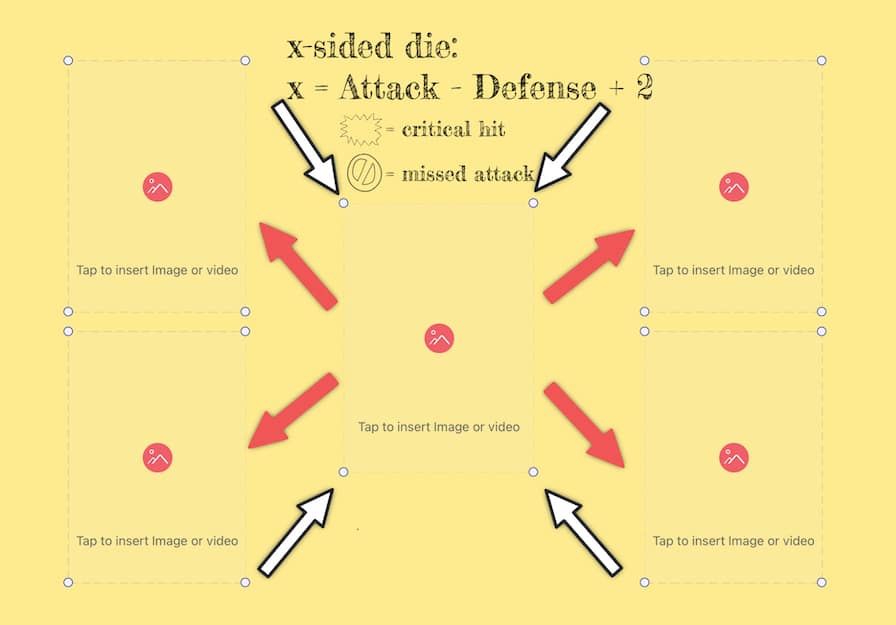

The third iteration of my battle sheet entirely lives in an Explain Everything project. It consists of five placeholders, where both player cards and enemy cards can be inserted. I also made various cliparts (one of the most underestimated features of Explain Everything online whiteboard, if you ask me!) and I also added 6 additional slides to my project. I normally do not use more than 1 slide, but for my battle sheet, I finally found a good use for slides that perfectly enhances my game. Slide 1 houses my character cards for each group of four students. Slides 2-7 each house a different dungeon. The actual game that we may play at the end of a successful lesson, or even during lunch break, starts with a student rolling a die. If they roll a 5, they’ll end up in Dungeon 5 – so I quickly jump to Slide 6. There, I’ve put a map. Each map currently houses 4 or 5 rooms my students can explore, and they are explored by rolling the die again. The final room, typically room 4, will house a boss battle which grants rare items and lots of experience points and gold.

Having constructed this file once, I quickly saved it as a template – another fantastic Explain Everything feature. So now, with a few simple taps, I can open up a new battle and I’ll have access to a randomly generated dungeon just like that. Even if we play five full rounds during lunch break, no two groups will even come close to exploring the same rooms, even if they do end up in the same dungeon. And to me, that really shows how versatile the Explain Everything whiteboard app is.

Explain Everything template for gamification in the classroom

I’ll be happy to share this project with whoever might be interested in it. All the artwork contained in it originated from pixabay.com and is royalty-free. I mostly just added an oil-paint filter to the images to give them unique flair. None of the pictures were taken by me but all of the cards including the frames are 100% created by me and can be used without an attribution. I’ll gladly add the template of my card in PSD format. If you know the basics of any advanced photo editing software such as GIMP, you’ll quickly understand how to change any single part of my template. I hadn’t used any such software in years but gamification made me look into it again and it’s been so fun finding a creative outlet. Future iterations of my game will have students help me create and design new items because ultimately, it’s their game. And they should have some agency.

Here’s an example of the game I created with Explain Everything:

And here’s the empty project that you can use as a template for your own game!

Tech tools that we need to learn

When I give presentations, other educators sometimes say things like “Well, that’s easy for you to say” – and that always bothers me a little bit. Why would the use of tech tools really come any easier to me than to anyone else? If I try a new app, I love messing around with it, trying out all the features, tapping through all the menus and buttons I see. That’s something I find fun and engaging. So in that way, tech might really come a little easier to me simply because I enjoy pushing buttons. But I have no natural talent that makes me a proficient user. It’s all about the time, effort and thought I put it into using it.

Just as with anything else – if you want to get good at using tech tools, you have to be intentional about it. Intentionality, effort and endurance are key.

If I decided to go back to university to continue my education, I’d be much more intentional about how I handled my notes than I was oh so many moons ago. If I were handed paper notes, I’d mark them up, digitize them and add them to an app with OCR technology. OCR, or optical character recognition, uses an AI to go over an image and makes its content searchable. Long story short, this method would allow me to safely store all my notes (even the ones that started out analog!) in my app of choice, and make all the knowledge that I’ve personally gathered just one keyword search away. As opposed to in dusty boxes in my attic! And that is just one simple benefit of using technology in the classroom that’s already available today – I can’t even imagine the new ideas that will spring up in years to come.

At this point, I want us to ponder our approach to tech tools for a second by comparing it to how a carpenter works. Most of us have favorite apps and tools, and we’ll see in a second how aptly named they are. A carpenter might have a favorite saw or a favorite hammer, too. But would they use it on a screw? Basically, I want to make the argument that we as teachers have to start thinking about how we use our tech tools by planning with an end goal in mind. If I know what I want to achieve, what kind of experience I want to create for my students, then I can figure out which tool would best serve that purpose. We need to admit to ourselves that not every problem is a nail and that – over time – we will have to increase the number of tools we’re comfortable working with. Like a carpenter, what we need is a tool belt or even a toolbox of tech tools that we’re comfortable using when the need arises. Don’t use the same app for everything if you have access to another one that is much better suited to the task at hand.

Paradigm shift – the importance of incorporating technology into the classroom

In this closing segment, I want to clarify what I mean when I speak of the coming paradigm shift. Keep in mind that this is not based on any specific science or research and merely depicts my view of things, so take these words with a grain of salt. To my mind, the last major paradigm shift in education occurred with the invention of the book press. This marked the emergence of widely-available schoolbooks and ultimately led to what one might call some kind of universal understanding of what a school is and what its purpose is.

The way I see our current situation at this end of the first quarter of the 21st century is that digital technology has arrived and is in the process of changing not only education, but our societies as a whole. We might still be arguing about whether using technology in our classroom is good or bad now, but I predict that within the next 5 to 12 years (hopefully the former, but who’s to say) that conversation will be over for good, because by then, all kinds of new technology will simply be a part of our daily lives. By then, technology in the classroom will simply be a fact of life, and using it skillfully will be a basic educational requirement. That’s why to me, the question really is: Do we want to spend the next 5 to 12 years fending off new technologies, or should we simply admit that changes are coming and embrace them? Why not use this moment in time to prepare for the future?

A message to other teachers

All this brings me to what I wish for our students’ future, which I will formulate as an invitation to my fellow educators:

Dear teachers, I urge you to embrace the coming change with me. Model what a lifelong learner is – let’s not just prepare for the future, but instead shape it together with and for our students with forethought, care and intentionality.

Five minutes of research is all it really takes to see how technology can be leveraged to foster inclusivity, facilitate accessibility and to provide scaffolding and asynchronous differentiation. Five minutes, and I’m certain you’ll be astonished by the vast potential out there waiting to be unlocked.

We live in times when we get the chance to not just react to coming changes, but to really set the course for the future of education. Possibly even more so than any previous generation of educators ever could have. And the joy, wonder and gratitude we exhibit for having this ability has the potential to set our students on a course of discovery as they too feel an excitement for all that‘s to come.

Sources

This is a very short list of great sources I have come across since I started my journey in gamification nearly a year ago. If you’re looking to get inspired, do check them out.

Free:

https://www.mrhebert.org/store.html

A fantastic educator sharing all his expertise for free. Follow this link and pick the “Teacher Guide” if you’re interested in two free ebooks. They were the first thing I read about gamification and they got me hooked.

Commercial:

- Daniel H. Pink – Drive (2009)

- Jane McGonigal – Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make us Better and How they Can Change the World (2010)

- Michael Matera & John Mehaan – Fully Engaged – Playful Pedagogy for Real Results (2021) (Very up-to-date research as well as various methods intended to be used in class. Both gentlemen have written solo novels about gamification well worth checking out.)

- WellPlayed Podcast hosted by Michael Matera (This has been with me on my commute for almost a year before I ran out of episodes. New episodes added weekly. Possibly my favorite resource.)

- Greg Toppo – The Game Believes in You (2015) (An absolutely amazing read not specifically intended for teachers but full of research showing how play affects learning. Should be part of any teacher education in my very humble opinion. Fantastic book if you’re interested in games and research about them.)